BLACK MAGIC

West Indies triumph in the first World Cup in June 1975, exactly fifty years ago, heralded a decade of global dominance, aided by the presence of their players in county cricket.

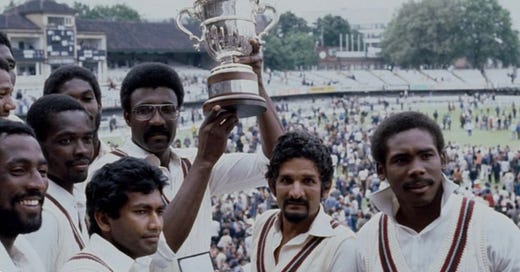

As Australia and South Africa battled it out at Lord’s in the World Test Championship final, I was sat with Sir Clive Lloyd, figurehead of that all-conquering West Indies team of the 1970s and 80s. Saturday saw a seminal moment in cricket as South Africa’s first black captain, Temba Bavuma, lifted aloft the World Test Championship mace, celebrated in our post-match podcast. And just as significant an achievement occurred exactly fifty years ago this week when Lloyd brandished the first (men’s) World Cup trophy.

There were other parallels too. The vanquished in both matches were Australia, and the victorious captain in each case made a telling contribution with the bat. Bavuma’s adhesive 66 gave South Africa hope and stability in the run chase in partnership with the superb Aiden Markram, building on the potency of Kagiso Rabada’s outstanding bowling. And fifty years before, Lloyd - known to all his teammates as ‘Hubert’ (his middle name) – pulverised the great Australian pair of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson on that very same 22-yard strip in the 1975 World Cup final.

Lloyd’s bludgeoning 100 - off just 82 balls – raised the bar for one-day batsmanship, four years before Viv Richards’ audacious 138 in the 1979 World Cup final. As can be seen from a few clips of his innings below, he assaulted those fearsome adversaries – who had just terrorized England’s batters in the 1974/5 Ashes a few months earlier – as if they were second division trundlers.

Lloyd and I sat in the Edrich suite at Lord’s reminiscing about that famous day: the exclusive interview we recorded can be found as a paid option on this site: a small subscription to The Cricverse will get you lots of premium content including a pre-release of our special 2005 Ashes podcasts series in early July.

The 1975 World Cup final was only the 33rd ever ODI but Lloyd had plenty of experience of one-day cricket of course, having played for Lancashire in the Gillette Cup and John Player League from 1969. He was one of the initial influx of West Indians that came to play in county cricket from then onwards and significantly raised the standards. A quick look at the leaders in the first-class averages for a random year (1981) reveals Viv Richards, Alvin Kallicharran, Gordon Greenidge and Lloyd in the top 15 of the batting, and Sylvester Clarke, Joel Garner, Michael Holding, Ezra Moseley, Malcolm Marshall and Wayne Daniel in the top 15 of the bowling. I still tremble at the memory of playing against any of those men (luckily Daniel was a Middlesex teammate and I only had to face him warming up in the Lord’s nets.)

The late 70s’ and 80s’ were, as has been often said, English cricket’s second Golden Age (the first was in the WG Grace era.) It was a glorious period for the game, and it was the West Indians – with the addition of the likes of Richard Hadlee, Imran Khan, Javed Miandad, Clive Rice, Mike Proctor, Barry Richards and many others – that elevated first class cricket to unprecedented levels. Noticeably however, few Indians. In the 1980s only Kapil Dev and Ravi Shastri had significant county careers.

That may be about to change. The investment in Hundred franchises by IPL owners (and purchases of entire counties in the case of Yorkshire and Hampshire) could initiate an influx of Indian players into county cricket. It is already starting to happen with Yorkshire signing Ruturaj Gaekwad – the captain of Chennai Super Kings - to make his championship debut in July. And Hampshire will shortly announce a prominent Indian signing to play in the county championship later in the month.

If the counties have any sense, more will follow. The abundant talent in Indian cricket can substantially raise the standard of the county game (they have a legion of fast bowlers, just like the Caribbean islands produced forty years ago) and counties should be able to afford them. More than that is the oft-used term ‘engagement.’ The way counties will become sustainable in the future is partly through commercializing their live streams and creating sponsored content for social media. That is where cricket is mainly consumed. The highlights of this World Test Championship final are online.

So what Indian cricketers bring with them other than skill and hunger are massive fan clubs. Gaekwad has 5 million followers on Instagram, other potential recruits are Yashasvi Jaiswal (4.6m followers) who spends much of the summer in England and new English resident Ravi Ashwin (5.4m followers.) When Yuzvendra Chahal took his first wicket for Kent in a one-day game last year, the video immediately got 600,000 downloads. With agile commercial teams and willing sponsors, this is where county cricket’s future prosperity may lie.

A word of caution, however. Inadvertently those brilliant West Indians of the 1970s and 80s used county cricket as a sort of finishing school. It helped make Lloyd’s and Richards’ teams practically invincible. A host of young Indians playing county cricket could herald a decade of Indian dominance.